Restorative justice is the idea that conflict occurs because of broken relationships. If relationships can be restored, conflict can be resolved without punishment, resentment, or continued animosity. WMRA’s Kara Lofton talked to three teachers who are bringing the practice into their classrooms.

[Video: Sounds of a teacher yelling]

That was one of almost 20,000 similar videos on YouTube of teachers or students yelling at one another. We don’t know what happens after the video ends, or what happened before it started that caused the teacher to lose his cool, but most commenters assume the kid eventually left the class and served some kind of well-deserved punishment.

But what if it was possible to prevent such a scenario in the first place?

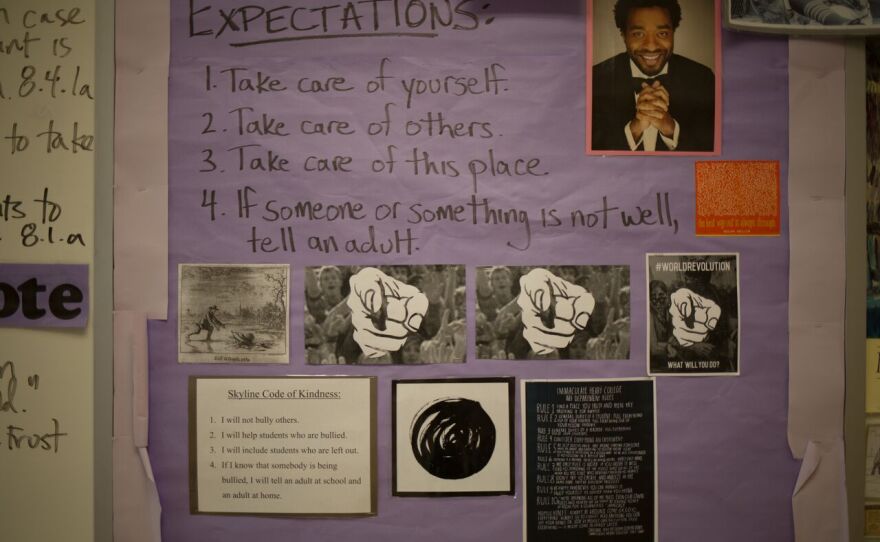

Sisters Allison and Carolyn Eanes both teach 6th grade English – Allison in Harrisonburg and Carolyn in Harlem, New York. Both use restorative justice practices in their classrooms, which is the idea that conflict often occurs because of broken relationships, not because students are actively trying to be “bad.” It is an alternative to the “zero tolerance” policies in place in many schools around the country, which educators like Rob Fennimore, another Harrisonburg-based teacher, say are not working.

ROB FENNIMORE: When I think about restorative justice I think about meeting needs and paying attention to the harm that’s caused all the parties involved. Let’s take the example of a child misbehaving in class whether toward another classmate or a teacher.

One way to solve that would be to remove or punish the student who is being disruptive.

But Fennimore says if he can remove himself from the equation (he said classroom disruption often feels very personal) and ask, “why is the child acting that way?” he can humanize the child as a complex being with struggles that may have nothing to do with the scenario at hand.

FENNIMORE: And then give the child who is acting up a chance to say why he or she is acting that way. I feel like in that moment some real magic can happen where the offending child can hear what he or she is doing wrong to others, the impact that’s having and for the person who is being distracted, or in my case as a teacher I can tell that child, “what you’re doing hurts me.” That’s a phrase that I’ve used a lot with kids rather than “get out!” or “you’re really making me angry!” I will often give the example of “what you’re doing hurts me,” and then give the example of why it’s hurting me.

But in order for that kind of restorative justice to work in classrooms, there needs to be a foundation of trust between students and teacher.

[Sounds of chairs moving]

In Allison Eanes’ sixth grade classroom in Harrisonburg, students are setting up chairs for a circle process. Eanes gets out her “talking piece,” (which for her is a little metal sun). Whoever is holding the talking piece is the only one in the circle allowed to speak.

ALLISON EANES: Welcome to the circle. Reminder of the guidelines: we are going to respect the talking piece, we are going to speak and listen with respect, we’re going to speak and listen from the heart, we are really going to try and be present today, and we are going to honor privacy.

Eanes does circles about once a week. They are a way for her to build trust with her students by facilitating an atmosphere of open, honest and safe communication. And the students really like it.

JAFAR MANSOOR: It lets us learn how to trust people, maybe they are just acquaintances or best friends, you still get to trust them and see if they can be trusted and if you can tell them anything.

That was Jafar Mansoor, one of Allison Eanes’ students. His classmate, Nega Salan chimed in. She said for her, the circle provides a safe space to speak openly and honestly without fear that classmates will gossip about her opinions. Jordan Perez, a third student, agreed.

JORDAN PEREZ: One of our rules is to honor privacy in the circle and so people know that we can trust them about when they share stuff they don’t want other people to know – they know they can trust us.

Carolyn Eanes came to teaching through social work. She said she saw that young people were continually being [quote] “shut down, dehumanized, marginalized and disempowered.”

CAROLYN EANES: It’s abundantly clear to me that those ways of working with young people and treating young people aren’t working and they certainly aren’t preparing them to be anything but future inmates in our criminal justice system I mean the school to prison pipeline is so clear to me how that functions. And so not only are many of our practices of militantly locking down schools and keeping kids in line and forcing them to take a million tests, those are obviously not working.

None of the three teachers claim that restorative justice will always work or that it is the only and best answer to conflict, but it is an alternative they find highly effective. Because when it does work, advocates say, trust is built, students stay in class and teachers are better able to do what they want to do – teach.